In the world of videogame journalism and fandom, no event towers higher than the Electronic Entertainment Expo, or E3. This annual tradeshow is provides game publishers a chance to hawk their wares to international buyers and game journalists, tastemakers and celebrities. For 14 years, David attended the expo, noting its spectacle and alternating between a gee whiz revelry and an sneaking suspicion he was being sold an opinion he didn’t hold.

This essay originally was presented as a paper at the Society for Media Studies in 2015. Originally, we thought the analysis of E3 fit well with a nuanced reading of how game journalism fit within the broader context of consumer culture. But for space, this essay would have appeared in the book. We think it still speaks well to how game journalism works with game fandom and inside the broader context of the FTG model.

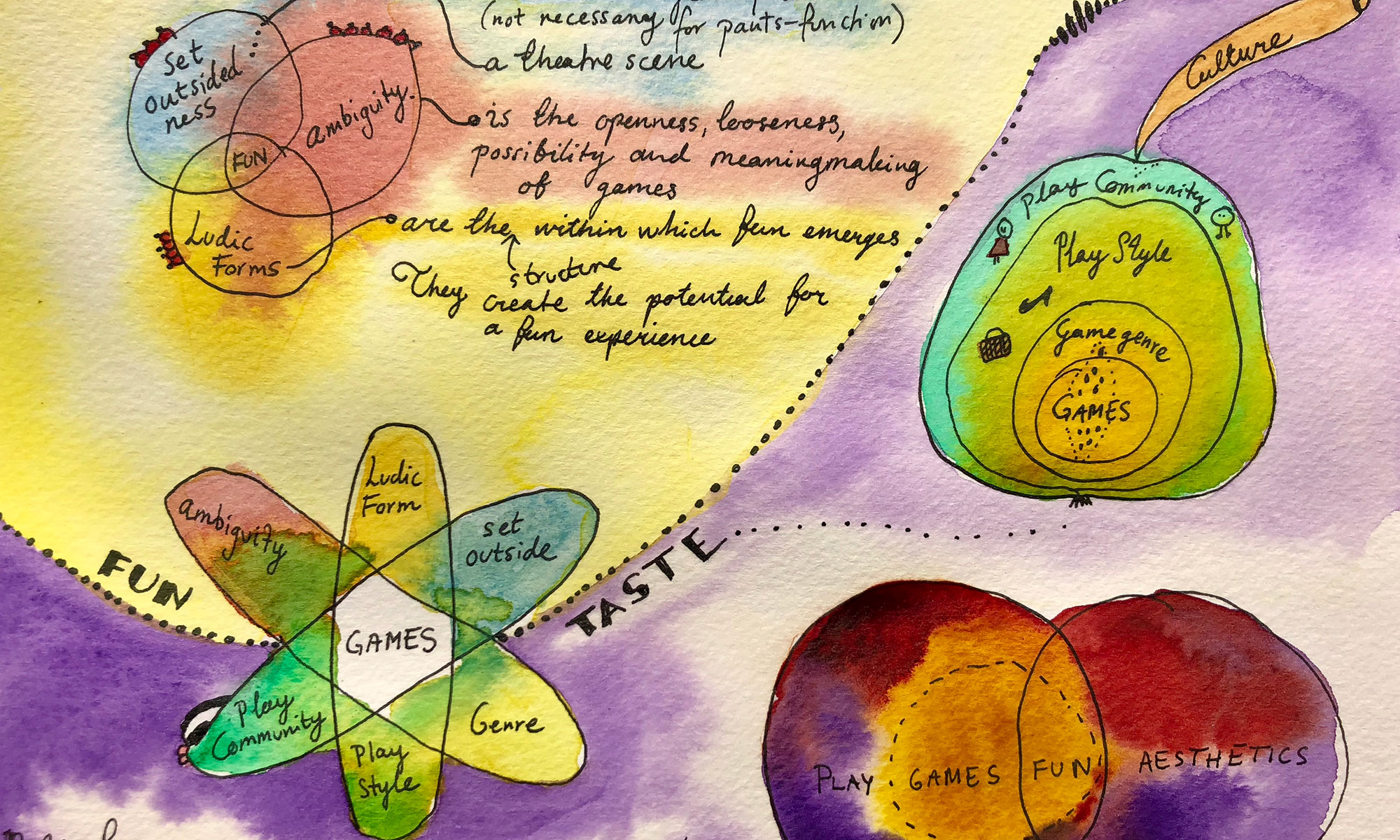

For more information on Fun, Taste & Games: An Aesthetics of the Idle, Unproductive, and Otherwise Playful (MIT Press 2019) see: http://ftgbook.com/

The Electronic Entertainment Spectacle

David Thomas

Does Debord’s spectacle help us understand the marketing of game tastes?

You couldn’t ask for more hyperbolic praise: An “orgy”[1],“circus” ”gala”, “a bacchanal”[2], “parade of pomp and circumstance”, even a “hallowed piece of the modern video gaming industry”[3] For 21 years the Electronic Entertainment Expo, or E3, has operated as the central marketing event for both game retail outlet buyers and journalists covering games. 2015’s annual show presented an estimated 1,600 new videogaming products to 52,000 visitors attending from 109 countries.[4]

But not everyone is fully dazzled by gaming’s most important spectacle.

“I hate you E3,” declared a particularly honest web headline.[5]

At first glance, it’s the usual blogger click bait. When you consider that the author is a videogame critic writing for a prominent national videogame website and that E3 is the gaming industry’s biggest and most important trade show, then you get the idea that headline claim clearly wants to speak to something out of the ordinary.

As a commentator on this article observed:

“The eye-catching title of an essay from the latest installment of The Escapist puts the emphasis on the negative aspect of the love-hate relationship many industry vets have with E3, but there’s surprisingly a lot of love for the trade show here, even if you don’t subscribe to the hardened ‘I hate E3 because I love it’ theory of convention devotion.”[6]

Whatever else is going on with E3, it clearly stirs strong emotions. And between the love and the hate we can pry open the event to better understand the nominal function of E3 and, more importantly, how the operation of this expo exposes key themes in the broader notion of mass media in general and in contemporary cultural taste in particular. Ultimately, what may save E3 from its harshest critique and criticism–best summarized as a sort of Debordian spectacle—is nothing more complicated than fun.

Not Another Trade Show

So, what is E3?

The Electronic Entertainment Association describes their event as “the world’s premier trade show for computer, video and mobile games and related products.”[7] Each year E3 fills the Los Angeles Convention center with multi-story booths, garish displays, glitzy celebrities and game demos. It is a party atmosphere of pounding sounds and pulsing lights attempting to turn the excitement and bravado of videogames into a real world sensorial overload. Or more colorfully, from a 2013 mainstream web article:

“In an effort to sell the idea of every game imaginable, E3 unlocks the collective psyche of culture and smears it over you like Vasoline. It’s the marketing equivalent of being churned up in a rolling beach breaker. And for the entire week of E3 you feel a little bit like you are having a psychotic episode.”[8]

In short, E3 turns up the volume in a targeted effort to garner attention and sell games. As Ars Technica editor Kyle Orland sums up, “From the mainstream media side, it’s the kind of thing that gets coverage and interest—NPR or the Washington Post. It’s that big spectacle that attracts people that would not normally cover games.”[9]

He continues.

“E3 is still the one. It has the history, all the big announcements. It holds a place in the imagination of the people that have not been there.”

While the videogame calendar is filled with other major and minor marketing events designed to sell games, peddle stories to journalists, cultivate fan bases and inspire retailers to stock product, E3 distills and concentrates those themes into a singular hyperbolic event. E3 is simultaneously the mythical Shangri La and the pilgrimage to Mecca of games.

E3, in a word, is spectacle. And on the point of this term, “spectacle”, we can place Guy Debord’s cultural scalpel. Borrowing ideas from this noted Situationist and Marxist critic’s most recognized work, “The Society of the Spectacle”[10], we can perform a precise and insightful vivisection of the world of videogames. Through Debord, we can separate, so to speak, the love from the hate.

Spectacle

Debord opens his analysis promising to do “deliberate …harm to spectacular society,” From here he launches the attack with the following words:

“The whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that once was directly lived has become mere representation.”[11]

There is a lot to Debord’s critique, but at its center sits a fairly traditional reading of Marx, complete with the ills of Capitalism and the alienation of the worker. The important update Debord offered is the notion of the spectacle. In his thesis, the mass media society has achieved, at dramatic scale, the destruction of social life and replaced it with the image. The image, in this case, is the tantalizing dance of the media and celebrity culture. This glitz and glare of the spectacle seduces us to consume image as a new form of reality. This consumed image becomes a sort of shadow commodity, replacing authentic and meaningful production. Combine this dematerializing of the material into image with the Capitalist focus on ownership, or what Debord calls “downgrading into having”, and you inherit a broken society in thrall of the image. It’s a pretty depressing picture and not far from the lowest levels of Plato’s Cave, flickering images passing for truth in front of prisoners chained underground, far for the true forms on the surface.

“For one to whom the real world becomes real images, mere images are transformed into real beings,” warns Debord.[12]

E3 as Spectacle

Just as E3 attempts to compress the videogame experience into a once-a-year, must-attend event, so does it work well as a site to view Debord’s society of the spectacle operating in concentrated form.

Notes one game writer, reflecting on E3: “This show is all about spectacle – think of it as Vegas for games and the party hardy mentality comes naturally.”[13] Or, even more telling, consider a description of an event held by the publisher Gathering of Developers. Its E3 sideshow event, the G.O.D. Lot, was designed as the ultimate tweak on the nose of an E3 viewed has having become too mainstream over the years:

“Within the parking lot’s fences are a shirtless rock bands, legions of strippers, dozens of dwarfs, hundreds of gamers and countless cups of beer. There are adults dressed as Vikings and commandos. People are slurring their words.”[14]

This scene provides a perfect tableau for Debord’s criticism. Here we have an almost unbridled fetishism of the videogame commodity, an image selling a product that praises only images, a spectacle created to support and augment the daily at-home spectacular ritual of videogame play. No wonder the stereotype of videogame life is the lonely player munching Doritos-brand tortilla chips in the glow of the television screen. Videogames have become a primary form of contemporary media because they reflect, in Debord’s words,

“…the historical moment at which the commodity completes its colonization of social life. It is not just that the relationship to commodities is now plain to see–commodities are now all there is to see; the world we see is the world of the commodity.”[15]

It seems we didn’t need virtual reality goggles to block out reality and repaint it. The spectacular society achieved this end already. And E3 is its grandest destination.

If that was not a harm apparent in and of itself, Debord presses the point when he calls the spectacle “no more than an image of harmony set amidst desolation and dread, at the still center of misfortune.”[16] I hate you E3, indeed.

E3, then, appears as an incubator of alienation and isolation. While fans clamor for bigger, badder and more explosive announcements and displays of commodity power disgorged by the big game publishers Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo, Debord sees this marketing clamor as “the ruling order (which) discourses endlessly upon itself in an uninterrupted monologue of self-praise.”[17]

‘Who won E3?’ becomes an annual journalism trope suggesting that someone, some company, will overtake the rest of the industry and win the prize of increased sales. “That’s the angle all the post-show analysis tends to take,” writes Mashable reporter Adam Rosenberg. “It makes sense; E3 is the one time of the year when the biggest pushers of games line up to tear the curtain off of blockbuster reveals.”[18]

The lonely gamer does not come to E3 to find society, only to watch as the PR machine crowns its seasonable winners. Rooting for a winner only further divides everyone into publisher, gaming console and intellectual property camps, something Debord sees as driving alienation, rather than emancipation.

“The spectacle is simply the common language that bridges this division. Spectators are linked only by a one way relationship to the very center that maintains their isolation from one another. The spectacle thus unites what is separate, but it unites it only in its separateness.”[19]

Game journalists charged with carrying the image culture of games from E3 back to the game consumers struggle with the alienating properties of the spectacle. Here we can see more accurately the hate side of the E3 love/hate dichotomy. On one hand, the spectacle delivers. It produces a fantastic commodity and hypes it into existence. On the other, as Debord warns,

“The spectacle’s function in society is the concrete manufacture of alienation.”[20]

And how could it be otherwise?

“(T)he business of videogames isn’t really about fun,” intones Spin Magazine. “It’s about money.”[21] A point hardly lost on Debord: “The spectacle is another facet of money, which is the abstract general equivalent of all commodities.”[22]

Following the “I hate E3” theme, Debord is ready with a solution. His remedy for the society of the spectacle was predictably Marxist, as sketched in the later work, “Comments on the Society of the Spectacle”.[23] Here he pointed to conspiracy, war, assassination and, eventually, revolution, as the cure for the ills of this society. Presumably, Debord would see no better solution to “the problem of E3” than its demise.

A Playful Revolt

To the average gamer, spectacle isn’t the problem, it is exactly the point. As gaming site Shacknews lamented:

“To some people, E3 is more like a chore than a week of kick-ass fun. Of course, why these people end up with passes instead of giving them to more enthusiastic parties is beyond us, but they live to complain about the toils of the event, or how worn out they’ll be afterwards, instead of, you know, enjoying it.”[24]

From a hardened Marxist perspective, perhaps this smacks of idealizing fiddling while Rome burns. Certainly, there is no reason to blunt Debord’s criticism. However, it helps to recall that Debord started his revolution in the playful art pranks of the Situationists International and ended his days working on a board game. Did Debord himself signal a more gentle revolution, a playful revolt?

By taking videogames as a special cultural case, as a hedonic and eudonic form of art and expression and entertainment indicative of our age, can we ask what is it about games that destroys the commodity, contradicts the alienation of the spectacle and restores a sense of social life? While Debord was convinced that art was dead and no longer a vector for revolution, perhaps games offer their own aesthetic approach, a playful revolution with a teasing détournement that frees the player?

An emerging understanding that games have long held their own aesthetics provides a platform for cleaving games from art in a manner that lets us address Debord. In contrast to the beauty-driven aesthetics of Kant, the aesthetics of games lies in the domain of fun. So here we suggest: Can an aesthetics of fun recover the Debordian critique? Can we play ourselves out of this mess?

Play theorist Bernard DeKoven argues this point in principle considering that “maybe because freedom itself is fun. Maybe fun itself is freedom.”[25]

He writes:

“Fun is at the heart of things – of things like family, marriage, happiness, peace, community, health; things like science and art, math and literature; like thinking and imagining, inventing and pretending.”[26]

E3 is a spectacle, to be sure. And as a spectacle, perhaps it does reflect some of our more base cultural constructions. Maybe we have given up something essential in the pursuit of mere image. But as a shrine to fun, maybe E3 is also calling for a higher cause.

This recalls John Beckman argument that points out that the joy of having fun remains a central force in the freedom-loving culture of the United States. For Americans, he argues, fighting for freedom was always had a flavor of the foolish, the pleasurable and playfulness of fun what he calls “joyful revolt”. To Beckman’s historical eye having fun in the face of more serious concerns marks a very American form of freedom.

If fun, unlike beauty, ties to freedom, then maybe the spectacle of E3 differs from the spectacle in Debord’s critique. Where Debord’s spectacle glossed over and covered up the fun, spectacle may open up and invite debate and participation.Debord wanted to tear down the spectacle through revolution. But it appears he never considered how the spectacle itself could be a part of the revolution. Looked at playfully, E3 is more than a brute force marketing juggernaut meant to roll over critique and objection. Instead, E3 is also a playground of sight and sound, a chance to fiddle with almost-complete games and grab glimpses of magical new worlds in development. Rather than totalizing reality with mere imagine, E3 instead taunts the limits of the grossly material, mocks the powerlessness of the individual in mass society and invites us to play, to delight and have fun together.

Debord wanted to dictate the hows and why of revolution. But games demand their freedom and their taste, their own small aesthetics. Certainly E3 sports its own artifice and vacuity and can act completely deaf to diversity. But to focus on what’s not there only misses the point enjoyed by the game players who honor what is. To those in on the fun, E3 tastes like the freedom to enjoy the image on their own terms, to express the personal and socially sharable spectacle at the core of gamer life. Rather than totalize the gamer experience in one loud marketing crescendo, E3 instead provides a noisy bazaar of aesthetic options, of choice and play style and taste. If E3 is anything to games, it’s not a consumerist Gesamtkunstwerk as much as it is a cacophony of gleeful choice.

-

Dean Takahashi http://venturebeat.com/2013/05/31/the-deanbeat-gamings-biggest-suit-gets-ready-for-the-craziness-of-the-e3-trade-show/ ↑

-

http://www.g4tv.com/thefeed/blog/post/713211/e3-for-complete-noobs-your-guide-to-all-things-e3-2011/ ↑

-

“E3 Is Obsolete, but It Doesn’T Matter.” Forbes, 8 June 2012, http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidthier/2012/06/08/e3-is-obsolete-but-it-doesnt-matter/#6c8a1bdf44e9. Accessed 24 Aug. 2016. ↑

-

Hewitt, D. (2015) E3 2015 CLOSES RECORD-BREAKING YEAR AS GLOBAL VIDEO GAME INDUSTRY COMES TOGETHER FOR PREMIER EVENT. Available at: https://static.e3expo.com/e3expo16/documents/e3-2015-wrap-up-final-6-18-2015.pdf (Accessed: 25 July 2016). ↑

-

http://www.escapistmagazine.com/articles/view/video-games/issues/issue_46/278-I-Hate-You-E3 ↑

-

http://www.engadget.com/2006/05/23/i-hate-you-e3-declares-escapist-writer/ ↑

-

https://www.e3expo.com/show-info/2895/about-e3/ ↑

-

https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2010/06/paste-goes-to-e3-day-1.html ↑

-

Personal communication, Feb, 2016 ↑

-

Debord, G. (1984) Society of the spectacle. Detroit: Black & Red,U.S.

(Debord, 1984) ↑

-

Debord’s work is organized into 221 individual thesis. Citations reference specific thesis rather than page numbers, Thesis 1 ↑

-

Thesis 18 ↑

-

Kevin, Kelly. E3 For Complete Noobs: Your Guide To All Things E3 2011. 11 June 2011, http://www.g4tv.com/thefeed/blog/post/713211/e3-for-complete-noobs-your-guide-to-all-things-e3-2011/. Accessed 26 Aug. 2016. ↑

-

Spin, “G.O.D. is Dead. Long Live G.O.D.” David Kushner, p.195 ↑

-

Thesis 42 ↑

-

Thesis 63 ↑

-

Thesis 24 ↑

-

http://mashable.com/2015/06/17/e3-2015/#SAu29RuhOiqo ↑

-

Debord (29) ↑

-

Thesis 32 ↑

-

Kushner p. 185 ↑

-

Debord (49) ↑

-

Debord, G. (2010) Comments on the society of the spectacle. Translated by Malcom Imrie. 3rd edn. London: Verso Books. ↑

-

http://www.shacknews.com/article/84853/five-reasons-why-people-hate-e3-and-why-they-should ↑

-

De Koven, B. (2014) A playful path. United Kingdom: Lulu.com. P. 220 ↑

-

De Koven, p. 25 ↑